The audits, press freedom and the perceived threat

The audits, press freedom and the perceived threat

Posted April. 02, 2001 11:51,

I find it difficult to criticize any action of the Korean government under the presidency of Kim Dae-jung. He has had a remarkable personal and public life.

When I served as executive director of Freedom House, we strongly protested his kidnapping and detention. Later, I was present at the creation of the Forum of Democratic Leaders of the Asia-Pacific (FDL-AP) where Kim Dae-jung played the central role. This was a statesmanlike effort to spur democratic development, not only in Korea but hroughout the region. The historic opening to a freer political system in Korea is readily visible. The democratic spirit and political freedom of the country has increased remarkably in the past few years.

The Nobel Prize was but international recognition of President Kim Dae-jung’s unique contributions. The award was also, I am certain, a sign of confidence that the president’s personal attributes would spur the extension of peace and democracy beyond the present borders of the Republic of Korea.

Freedom House has noted, over the past decade, the significant improvement in the level of personal freedom of the citizens of Korea. Our annual survey of the level of political rights and civil liberties in all countries regularly included our analysis of Korea’s development.

In 1973, Freedom House regarded Korea as "not free." The political system was highly restrictive. The news media were closely influenced or controlled by the government. Significant improvements were noted in Korea from 1975 to 1987. Our comparative rating then placed the country in the "partially free" category for political rights and civil liberties.

Soon afterward, notable improvements in the electoral system and in the general opening of the society moved the country’s rating to "free." Through the intervening 14 years, despite occasional backward trends, Korea has remained in the category of free countries. Its democratic system was never rated higher than in the past several years.

Significant criteria of the general level of freedom in a country is the manner in which the news media are treated by officials of the government. Officials, after all, have considerable power to assure that news of government activities is fairly released to the public; that newsprint and distribution systems are fairly operated for all publications. They can also assure journalists that they can report and edit without fear that criticism of officials or of official policies will result in restrictions of journalistic freedoms. For, ultimately, both officials and journalists are servants of the people.

As with all governments, even the most democratic, however, there can be missteps by the bureaucracy. My year-round monitoring of the level of press freedom in every country has brought me to Korea several times during the harsh periods of undemocratic rule. I recall speaking with editors and an Information Minister who confirmed that there had been daily telephone calls from the government to editors. Journalists were advised---indeed, directed---what stories to cover, how to cover them, and even where to place them in the newspaper. Happily, those days are past.

But there can be far more subtle ways to influence the press. In a free market society such as Korea, newspapers must be financially viable. Any challenge to the economic strength of the press can be as damaging as a censor’s restriction on presenting news. Indeed, threats to the economic freedom of the press can be a highly sophisticated way of influencing the content of the news media. That is a danger to the stability of a free society.

Journalists and publishers are highly sensitive to any challenge to the freedom of the news media. Indeed, journalists live and work in a climate of daily tension. News deadlines come up speedily. Competition from other media is intense. The flow of news from the new sources of electronic delivery increase the tensions. To make the life of a journalist all the more difficult, the economic pressures from rising costs, shrinking markets and competitive advertising sources add significantly to the daily problems of meeting news deadlines and, at the same time, keeping the business side of journalism profitable.

Amid all these tensions, the publishers of major newspapers---their sensitive antenna alert---have perceived a harsh challenge to their economic freedom. And that, as they perceive it, translates immediately into a challenge aimed at the very freedom of the newspaper itself.

The tax audits of nearly two-dozen newspaper companies is regarded as just such a threat. The National Tax Service has said these are routine examinations which are not intended to influence the content of the news media. But when such audits are undertaken on this scale the news media, understandably, believe they are being targeted for their occasional opposition to government policies. The audits challenge not only the financial operation of the press but, as well, the essential role of advertisers in supporting a free press. Harsh criticism of journalists by officials can readily be linked to the widespread audits. Together, journalists may assume the audits are aimed at subduing press analysis and criticism. Such an economic threat---with inherent implications for press controls---if they exist in reality or even if they are simply so perceived by the press, is not a healthy condition in a free society.

All institutions and individuals are expected to provide their fair share of taxes. Abuse of the taxing and auditing authority, however, can be harmful to the very society a democratic government is committed to strengthening. An outsider looking in can hope that a quiet meeting among the relevant government leaders and the press would dispel the antagonistic perceptions and reinforce one another’s trust.

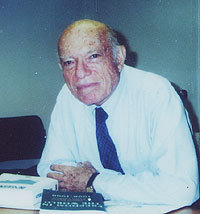

Mr. Sussman, senior scholar in international communications of Freedom House/New York, was executive director of the organization for many years. He is also professor of international communication at Columbia University’s school of international and public affairs.

Headline News

- Joint investigation headquarters asks Yoon to appear at the investigation office

- KDIC colonel: Cable ties and hoods to control NEC staff were prepared

- Results of real estate development diverged by accessibility to Gangnam

- New budget proposal reflecting Trump’s demand rejected

- Son Heung-min scores winning corner kick