Survival of humanity depends on reducing greenhouse gas

Survival of humanity depends on reducing greenhouse gas

Posted September. 12, 2020 07:20,

Updated September. 12, 2020 07:20

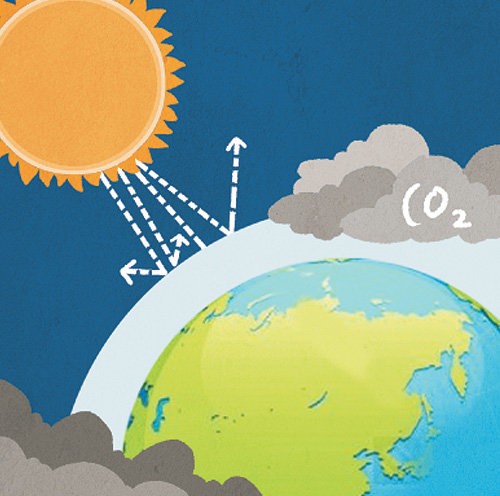

Human lives will likely be put at stake if the international community as a whole fails to reduce average temperatures to pre-industrial levels. We are already aware that the key lies in cutting back on fossil fuels that burn to produce carbon dioxide and, consequently, cause global warming. Nevertheless, it is not easy to make it happen. Fossil fuels have a wide range of uses not only across various industries but also in our daily lives. So much so that, modern-era lifestyles are often likened to carbon addiction. There is only so much we can do to reduce carbon emissions on our own initiative. Like or not, legally binding systems matter. That is, we need to put laws in place to resolve climate change.

The highest court of the Netherlands ruled in favor of the environmental NGO Urgenda in a lawsuit against the Dutch government last December, concluding that the defendant Dutch government must reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 25 percent of the 1990 levels up to the year 2020. In another environmental lawsuit filed by a civic group against the Irish government in July, the court ruled that the defendant must demonstrate an implantation plan to shift to a low-carbon economy by 2050. This month, six young Portuguese green activists filed a lawsuit against 33 nations including the European Union with the European Court of Human Rights. The plaintiffs’ argument is that the defendants have not paid sufficient attention to carbon reduction, thus infringing on the right to life of their own and family. As such, a growing number of citizens have recently brought governments to court for their failure in addressing climate change.

The United Nations has taken the lead in establishing a legal framework to regulate climate change at the global level. However, we are not able to expect potent legal force that comes before national sovereignty given that the U.N. runs within the international order that works around countries. Although the Paris Climate Agreement promotes U.N.-level legal regulation, it is limited merely to hoping that governments may implement the self-written Natonally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

A public figure with in-person experiences in South Korea and Europe once explained to this reporter about the differences in how two of them see legal systems. As the person put it, law is considered the ultimate goal to reach in South Korea while it is seen as a set of minimum rules to obey. That is why those who do illegal acts come under harsh criticism in Europe but the same level of violation of law does not cause the equivalent level of guilt in South Korea. It was hard to completely confront although I took the perspective as a mere opinion of a single individual. The South Korean government submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) its NDC to reduce carbon emissions to 37 percent of business as usual (BAU) levels by 2030. Having said that, it is a grand goal to make come true. Considering the patterns of increasing carbon emissions, it seems like a far-fetched dream.

“Pacta sunt servanda” is a Latin phrase that serves as one of principles of European law. It explains respect for law that makes European nations feel it obligatory to keep their promise to the international community to realize their NDCs even if the U.N. does not enforce any legal compulsion. Another fundamental phrase is “Fiat Fiat justitia ruat caelum,” meaning, “Let justice be done though the heavens fall.” Extreme weather events, as a result of climate change, have recently been troubling the globe. It only demonstrates that the climatic system of the planet is not working properly. To help recover the impaired climate system, it is important to materialize legal commitments as promised to the international community. It is the path we should walk to ensure the survival of the human race.

Headline News

- Joint investigation headquarters asks Yoon to appear at the investigation office

- KDIC colonel: Cable ties and hoods to control NEC staff were prepared

- Results of real estate development diverged by accessibility to Gangnam

- New budget proposal reflecting Trump’s demand rejected

- Son Heung-min scores winning corner kick