Fitch downgrades U.S. credit rating to AA+ amid fiscal concerns

Fitch downgrades U.S. credit rating to AA+ amid fiscal concerns

Posted August. 03, 2023 07:47,

Updated August. 03, 2023 07:47

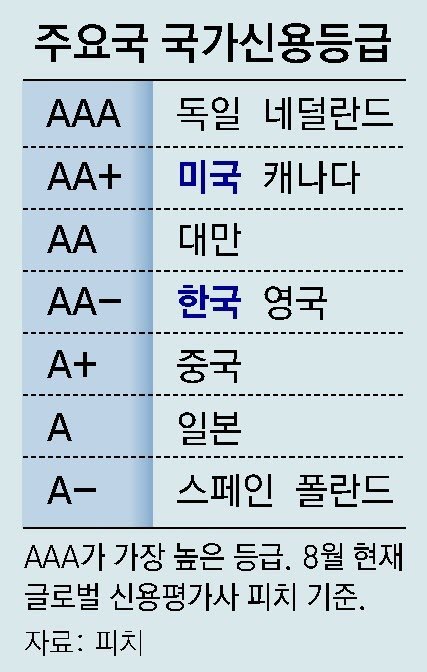

Fitch, one of the world’s three major credit rating agencies, has downgraded the United States’ credit rating from AAA to AA+, marking the first such downgrade in 29 years in 1994. Such a downgrade by other credit rating agencies came 12 years after Standard & Poors (S&P) previously downgraded the rating in 2011. Moody's is the only agency still maintaining the highest AAA rating for the U.S. The credit rating downgrade has far-reaching implications as it means that the U.S. will face higher interest rates when borrowing through the issuance of treasury bonds.

Fitch’s decision was prompted by its concerns over the projected fiscal deterioration and the mounting debt burden of the U.S. federal government over the next three years. It also pointed out the frequent conflicts arising whenever the U.S. government seeks authorization for a new debt ceiling from Congress. As of now, the national debt to GDP ratio for the United States stands at 112.9 percent, up from 100.1 percent in 2019, primarily due to the surge in government spending during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen criticized the rating agency’s decision as “arbitrary.” However, the downgrade is expected to have ripple effects on the U.S. Treasury yield, traditionally considered one of the safest assets, and may cause confusion in the global financial market. The 2011 downgrade by S&P led to a 15 percent drop in U.S. stocks and a 17 percent drop in Korea’s stock market within a week. Nevertheless, some analysts believe that this time, the impact may be more subdued as the global market had already anticipated the possibility with Fitch’s advance notice, and global shares had started on a weak note.

The news serves as a clear implication for South Korea as well. The country’s fiscal soundness has weakened, and the price must be paid. Over the past five years, South Korea’s sovereign debt has increased by more than 400 trillion won, and it is on track to surpass 1,100 trillion won in 2023, marking the fastest pace of increase. The soaring household debt, which ranks high among the world’s leading countries, and the rapidly aging population have contributed to the downgrade. Additionally, South Korea’s economic growth engine, its exports, has remained sluggish, while its potential growth rate has declined and is expected to fall to the 1 percent range by 2030.

South Korea stands out as a country with little intention to regulate its sovereign debt compared to other OECD countries. Credit rating agencies have recommended adopting fiscal rules to limit the fiscal deficit to 3 percent of annual GDP. However, the country’s political circles are hesitant to implement such rules, and the chances of their adoption in the National Assembly remain low. Opposition parties, focusing on next year’s general election, advocate for increased spending, despite potential reductions in taxes and increased spending. If this trend of imprudent fiscal policies continues, South Korea’s already precarious AA-rating may be at risk of further downgrade.

dhlee@donga.com

Headline News

- Joint investigation headquarters asks Yoon to appear at the investigation office

- KDIC colonel: Cable ties and hoods to control NEC staff were prepared

- Results of real estate development diverged by accessibility to Gangnam

- New budget proposal reflecting Trump’s demand rejected

- Son Heung-min scores winning corner kick