France must confront its Olympic debt issue

France must confront its Olympic debt issue

Posted August. 19, 2024 08:42,

Updated August. 19, 2024 08:42

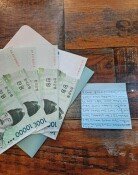

The 2024 Paris Olympic Games wrapped up on August 11 (local time), and France still feels the festivities' lasting presence. Swimmer Léon Marchand, a four-time Olympic champion, is being talked about as a national hero. Olympic merchandise remains popular as a reminder of the triumphs. Even the socks and scarves from the volunteers' sweaty uniforms are selling for a fortune on online secondary markets.

The party was over, and the news came that threw cold water on champagne-soaked France. Five days after the closing ceremony, President Emmanuel Macron announced that he would hold a series of meetings with opposition leaders on Friday. This attempted to open the door to discussions on long-pending national issues. Among these, the fiscal deficit is a major concern. The country's debt is so high that the deficit has become severe. France's government debt as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) was already projected to reach 117.3% in 2022, well above the average for OECD member countries (78.6%).

The French Court of Audit (Cour des Comptes) criticized the Élysée Palace, the presidential office, for its spending. The Court of Audit released an audit report on the Élysée Palace's budget on July 29, before the Olympics were even over, highlighting a deficit of 8.3 million euros (about KRW 12.4 billion). The report specifically pointed to the costs of a dinner for King Charles III and a dinner for Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi last year. It also revealed that 12 non-refundable business trips were canceled, costing more than 830,000 euros (about KRW 1.2 billion).

The Élysée Palace's extravagant spending is just one example. A more fundamental cause of France's budget deficit is the government's misguided economic growth forecasts and unrealistic fiscal goals. The government was overly optimistic about economic growth and overestimated tax revenue, leading to a loosely constructed budget. The deficit reduction targets were also unrealistic. The government ambitiously aimed to reduce the deficit to '3 percent of GDP' as recommended by the European Union, but it was only reduced to 5.5 percent as of last year.

France's national debt and fiscal deficit pose a major threat to the economy. With a declining birthrate and aging population, the government has many areas in which to spend money, but it is doubtful whether enough revenue will be earned. France's economic growth is expected to remain below 1 percent until next year. The international credit rating agency Standard & Poor's (S&P) downgraded France's sovereign credit rating to 'AA-' from 'AA.' This is the first downgrade in 11 years since 2013.

The challenges France faces with its national debt and fiscal deficit could also occur in Korea in the future. Firstly, the Korean government has struggled with forecasting tax revenues. Last year, the error rate—the difference between the government's tax revenue forecast and the actual amount collected—was 14.1 percent. This is not a one-time mistake; the government's error rate has doubled for three consecutive years.

Both the ruling and opposition parties are proposing fiscal easing policies in the face of tax revenues falling short of expectations. Recently, the head of the French Court of Audit told Parliament that “solving the fiscal deficit is not a matter of left or right, but a matter of common interest.” The Korean National Assembly should take note. We need to hear more blunt truths like this in Korea.

Eun-A Cho achim@donga.com