US cuts rates while China and Japan freeze rates

US cuts rates while China and Japan freeze rates

Posted September. 21, 2024 07:29,

Updated September. 21, 2024 07:29

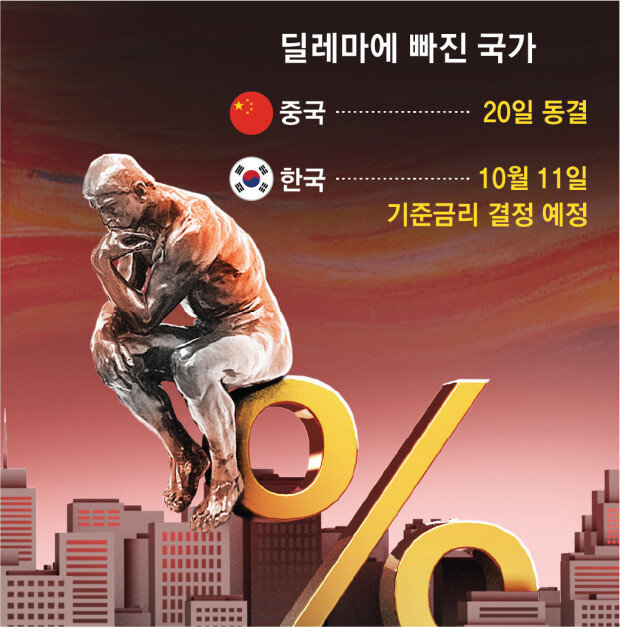

While the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) lowered its benchmark interest rate for the first time in four and a half years, signaling the end of the tightening cycle, central banks around the world have taken different paths. Immediately after the Fed’s ‘big cut’ of 0.5 percentage points, Middle Eastern oil producers such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia followed suit. They cut their rates, while the U.K., Japan, and China kept their rates on hold, taking a ‘breather’ to observe the market.

On Friday, China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China, also said it would keep its one-year loan prime rate (LPR), the country’s benchmark rate, at 3.35 percent and the five-year LPR at 3.85 percent. The bank lowered the one-year and five-year LPRs by 0.1 percentage points each in July this year but kept them unchanged for two consecutive months in August and September.

It contrasts with market expectations that China would follow suit after the Fed’s rate cut. Of 39 experts surveyed by Reuters, 27 expected China to cut the LPR this month. However, the unexpected decision to freeze the rate was made because China's financial sector is still quite distressed. The net interest margin (NIM) of private Chinese banks hit a record low of 1.54 percent at the end of June. A further reduction in NIMs as a result of the rate cut could accelerate financial distress.

On the same day, Japan’s central bank, the Bank of Japan (BOJ), also kept its key interest rate unchanged at 0.25 percent. In March this year, Japan raised rates for the first time in 17 years since 2007, moving out of negative interest rates. Four months later, in July, it raised rates from 0-0.1 percent to 0.25 percent. The hike was followed by turbulence in financial markets in early August, with the yen strengthening and stock prices plunging. It raised concerns that the competitiveness of Japanese companies’ exports would suffer, prompting the BOJ to wait and see before deciding whether to raise rates further.

Central banks around the world are making varying choices as they face different challenges, including inflation and the level of distress in their financial markets. “There is less synchronization in this cycle of cuts than there was two years ago, when the world’s central banks aggressively raised rates together to fight inflation,” the New York Times wrote.

신아형 기자 abro@donga.com

Headline News

- Joint investigation headquarters asks Yoon to appear at the investigation office

- KDIC colonel: Cable ties and hoods to control NEC staff were prepared

- Results of real estate development diverged by accessibility to Gangnam

- New budget proposal reflecting Trump’s demand rejected

- Son Heung-min scores winning corner kick