Silent struggle of 'current young generation'

Silent struggle of 'current young generation'

Posted November. 02, 2024 07:19,

Updated November. 02, 2024 07:19

Imagine being a manager who is having a meal with a new employee who just graduated from college. You ask the young employee, “What do you think about the recent dopamine addiction?” It is likely a bias if you imagine him boldly expressing his opinion. Based on the author’s experience, the statistically correct answer is this: “They act like they are frozen.”

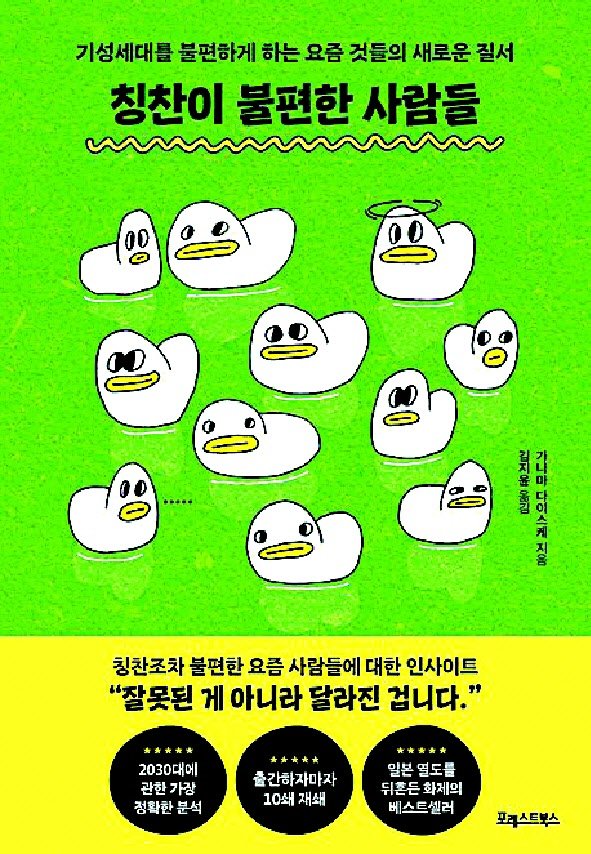

The book analyzes the ‘current youth’ of Japan, who are different from the ideas of the older generation. They are energetic on the outside but do not really have anything they want to do, and they try to bury themselves as much as possible. They are cooperative but do not do more than what they are told. The age range is assumed to be college students to those in their early 20s. The author, a professor at Kanazawa University in Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan, has detailed anecdotes from his own experiences at school and in companies.

It presents various quizzes and thought experiments to shatter the younger generation's perception. The flat label of the MZ generation (millennials + Generation Z) has given them an image of being enterprising. However, the book says that they “feel strong fear and stress about the act of making decisions” and “control adults by exuding an image of sincerity but refraining from unnecessary words and actions.”

It also directly refutes the expectation that they would hate company dinners. Although they value their private lives and are not interested in career advancement, the rate of company dinner attendance is on the rise again, breaking away from the long-standing downward trend. The author explains that “young people who want to be good kids do not have a strong enough self to firmly refuse, and it is easier to fit in with those around them.” The author supports his argument by presenting survey results conducted by the Japanese government and others here and there.

Some parts feel distant from our country's reality when dealing with young people in Japan. However, in that it points out yutori education (education that emphasizes experience rather than rote learning) and economic recession as the causes of the “good kid syndrome,” this book provides many implications for Korea, which is following a similar trend.

이지윤 기자 leemail@donga.com

Headline News

- Former commander's notebook includes potential plan to incite N. Korean attacks

- Constitutional Court to proceed with impeachment trial on Friday

- Deputy PM confirms next year’s under 2 percent growth projection

- Ukraine says Russia uses fake IDs to hide N. Korean troops

- Pres. Yoon refuses impeachment documents for a week